One of the points I offer in this blog and elsewhere is to be skeptical to assume that something is true because we think it should be.

We’ve been brainwashed to believe that obesity is a killer, despite research performed this year concluding that a little more weight may add life to your years. Many argue that an assault weapons ban will save lives despite the absence of social science research that supports this. Fewer guns should save lives, right? When skeptics like me point to Chicago which boasts extremely strict gun control legislation while being a murder theme park, we are given excuses to reject the data that contradicts gun control dogma. Isn’t the term assault weapon itself unfairly charged and loaded? I have supported medical education reform advocating that medical residents and interns should not be worked to exhaustion and yet be expected to administer high quality and compassionate care to ill patients. I had believed that somnambulating medical interns were more likely to harm patients with careless care. I believed that this was true because it seemed entirely self-evident.

Two recent studies published in the 3/25/13 issue of JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, suggest that I was wrong.

What should one do when a study contradicts a long held view? Two choices to consider.

(1) Reflect, consider the quality of the new information and modify your view.

(2) Attack the study as a Big Government, Big Oil or Big Anything conspiracy and hold your ground.

The latest information suggests that interns and residents who work fewer hours commit more errors.

Reasons include:

- While residents work less at the hospital, they aren’t sleeping more.

- Residents are now required to do the same amount of work in fewer hours.

- Shorter shifts mean more ‘hand-offs’ of patients to the next crew of eager interns.

Obviously, cramming in the same amount of high-pressure work into fewer hours invites errors, particularly with relatively inexperienced physicians who may not be adequately supervised at night. Medical handoffs are the event when interns who are leaving the hospital sign over the care of their patients to the next crew who must assume immediate responsibility for patients they may have never seen. Hospitalized patients are complex. The nuances of their condition cannot be seamlessly transmitted to a doctor-in-training in a few sentences. An intern may have to assume care of 10 or so new patients as he comes on shift. Would you feel at ease if you were one of these patients? Indeed, one of the defenses of the pre-reform system when interns were real men and worked until exhaustion was that there were fewer dangerous medical handoffs.

Now, these two studies are not determinative. The increased error rates with shorter work shifts were volunteered by the doctors themselves, which is not scientifically rigorous. I’m not ready to abandon my view that interns in my day were unnecessarily overworked, but it may be that the reforms that are in place left now have left us too far from a humane end zone.

Not every hypothesis needs to be tested. Do we need a study to determine if highway driving while wearing a blindfold is dangerous? Are we still entertaining the notion that it is better for patients and young physicians to meet when the doctor is disoriented from sleep deprivation? Is there really a need to torture interns to buck them up for their later years in medical practice when they will likely sleep soundly through most nights?

I’m against torture, even though I know its definition has been a matter of public debate. Indeed, I’m pleased that my views coincide with national policy.

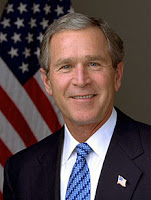

“We Do Not Torture”

“We Waterboarded U.S. Soldiers so it’s not Torture”

What if our senators and representatives had to legislate on four hours of sleep each night? Care to predict the outcome? Would the quality of legislation, comity and bipartisanship flourish? One would surmise that exhausted congressmen would commit more errors, but who knows? I say, let’s try the experiment for a year to test this hypothesis which may ultimately improve the political process. I think there’s a reasonable prospect that congressional sleep deprivation may improve quality considering that these self-promoting, self-aggrandizing, self-serving and self-protective scoundrels have already hit bottom. There’s only one direction they can go. No need to sleep on this one.