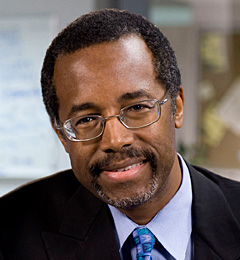

Dr. Ben Carson made quite a splash at the National Prayer Breakfast the other day. Elsewhere I discuss the moral vision he provides in his book, America the Beautiful: Rediscovering What Made This Nation Great. But here I want to look at his recommendations for health reform.

Dr. Ben Carson made quite a splash at the National Prayer Breakfast the other day. Elsewhere I discuss the moral vision he provides in his book, America the Beautiful: Rediscovering What Made This Nation Great. But here I want to look at his recommendations for health reform.

Most people who saw the speech were thrilled (or appalled) that he called for universal Health Savings Accounts beginning at birth. This is a fascinating idea that would merit some deeper analysis. Unfortunately, he doesn’t mention it in his book, even though he devotes a chapter to health care.

Instead, his writing offers up some off-the-cuff emotional reactions to problems he has experienced. They are not well thought through and I expect he would write something very different if he had an opportunity to dig a little deeper. Let me start that rethinking here.

He then describes one of the problems of providing free health care — poor attitudes on the part of patients. He says their sense of entitlement turns them hostile, and even abusive, toward providers:

Contrary to popular belief, one of the reasons many physicians refuse to see indigent patients is not that they cannot pay, but because of the poor treatment they receive from such patients.

He goes on to complain about the complexity of dealing with many insurers:

Unfortunately, our healthcare insurance system has become so complex that virtually all medical offices and larger practices need billing specialists just to navigate its intricacies. All of this variation and complexity produces mountains of paperwork and requires armies of people to push it around.

He thinks this is all done to prevent fraud. But he says a better remedy would be to impose very stiff penalties on those few providers who engage in fraud, “such as loss of one’s medical license for life, no less than ten years in prison, and loss of all of one’s personal possessions.”

Yikes! The family members of such a doctor would not be very happy about this. But, more importantly, what is called “fraud” is often nothing more than a billing dispute. Indeed, just a few pages later, Dr. Carson relates the story of a physician friend who wanted to get into real estate development, so he sold his oral surgery practice to a colleague. Medicare decided the colleague was engaged in fraud, but he didn’t have many resources, so they went after Carson’s friend as well:

They meticulously examined fifteen years of his practice records for evidence of fraud and were only able to uncover two questionable bills, amounting to a total of $180…He was told that they would take him to trial as a co-defendant with the buyer of the practice and would convince jurors that he had knowledge or turned a “blind eye” to the other doctor’s activity. And that eventually he would end up in federal prison if he did not plead guilty to a federal offense in connection with the $180 discrepancy…He accepted their deal and was sentenced to a one-year house arrest and a $300,000 fine.

This is how Medicare often operates. It chooses not to do simple claims adjudication before paying bills, so every five years or so, it makes a big public relations splash of criminally prosecuting providers who never should have been paid in the first place.

Also, to reduce paperwork Carson would have all payers pay all providers the exact same rate, regardless of their skills or underlying expenses. And he would require all insurers to “become non-profit service organizations with standardized, regulated profit margins.”

He would also “remove from the insurance companies the responsibility for catastrophic healthcare coverage, making it a government responsibility.” He thinks this would make coverage more affordable, because “if we did not regulate utilities, few people would be able to afford their water or electricity.” He would confine insurers to “a 15 percent annual profit, 5 percent of which would go to the government’s national catastrophic healthcare fund.”

Readers of this blog know that I am no great fan of health insurance companies and would like to see their role in health care greatly reduced. They are far too intrusive into the patient/physician relationship and have indeed piled on vast amounts of administrative costs to the entire system. The idea of universal HSAs Dr. Carson presented during his speech might help remedy all this but the ideas presented in the book are poorly informed:

- Insurers don’t currently make anywhere near 15 percent profits, more like 4 percent.

- Five percent of claims wouldn’t come anywhere close to funding catastrophic expenses.

- Not-for-profit insurance companies are no more efficient, accountable or affordable than for-profit ones.

- Utilities make a whole lot more money by selling services to the masses than they could by raising prices so that only a few could afford it.

- The reason utilities are regulated is because they are state-sanctioned monopolies not subject to the discipline of competition.

- Using criminal fraud to deter false claims is already being done in Medicare, with poor results.

After his prayer breakfast talk, some people thought Dr. Carson should run for president. That is a terrible idea. We don’t need more politicians, but we could use a great moral leader like Billy Graham or Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. Carson’s gifts would be wasted by descending into the weeds of public policy and practical politics.