Summary: In our project crowdsourcing healthcare prices in partnership with MedPage Today, we were asking primarily for cash or self-pay prices — but one of the most interesting shares we got was from a provider who wanted to tell us reimbursement rates. This post appeared originally in MedPage Today, where I wrote it as part of our pricing transparency partnership with MedPage Today. Re-posted with permission.

Reimbursement rates from payers are, of course, not available publicly in any easy or rational way. Sometimes you find out after the fact; some providers and insurers offer “transparency tools” but they are often wrong or hard to use. So the patient (or consumer, or individual) is often not able to know what the insurer will pay until after the fact.

So when we asked for providers to share prices, we were expecting that providers would send us cash or self-pay prices, and we have received several of those.

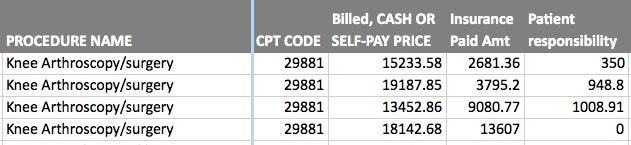

But, interestingly, Sutter Maternity and Surgery Center of Santa Cruz for Peninsula Coastal Region Sutter Health, sent a spreadsheet with charged rates, reimbursement rates, and patient responsibility for a selected group of procedures at the hospital (see below). It’s an acute care hospital with 22 beds, said our contact there, Meggie Rhodeos, the business services manager, who said she was sending us the data at the request of the CEO, Stephen Gray.

Here is what she sent:

- Knee arthroscopy: Charges from $13,452 to $19,187; insurance payments from $2,681 to $13,607. Difference: a factor of 5-plus.

- Repair initial inguinal hernia (No. 1 and No. 2): Charges from $13,950 to $22,184; insurance payments from $2,515 to $12,281. Difference: a factor of almost 5.

- Colonoscopy and biopsy: Charges from $1,552 to $2,320; payments from $849 to $1,773. Difference: a factor of 2-plus.

- Carpal tunnel surgery: Charges from $9,694 to $11,721; payments from $1,953 to $7,079. Difference: A factor of 3.6.

- Cataract surgery with intraocular lens (IOL): Charges from $10.456 to $12,831; payments from $2,474 to $8,024. Difference: A factor of 3.2.

Each one submitted is for a different patient with different insurances, she explained in an email. They wanted to be sure they gave the full range, she added.

How were these procedures and patients chosen? Rhodeos said they chose common CPT codes from a range of patients over the last two months or so. The listing is not exhaustive but representative, she said.

This is top and bottom for each procedure, she said, adding that the billed prices are fairly consistent but vary a bit for every episode of care because every patient is different. (Editor’s note: Here is a sampling of the rates she sent, followed by a discussion. Only one of these charts was posted in the original MedPage Today version of this article.)

Knee arthroscopy: Charges from $13,452 to $19,187; insurance payments from $2,681 to $13,607. Difference: a factor of 5-plus.

Repair initial inguinal hernia (No. 1 and No. 2): Charges from $13,950 to $22,184; insurance payments from $2,515 to $12,281. Difference: a factor of almost 5.

Repair initial inguinal hernia (No. 2).

Colonoscopy and biopsy: Charges from $1,552 to $2,320; payments from $849 to $1,773. Difference: a factor of 2-plus.

Carpal tunnel surgery: Charges from $9,694 to $11,721; payments from $1,953 to $7,079. Difference: A factor of 3.6.

Cataract surgery with intraocular lens (IOL): Charges from $10.456 to $12,831; payments from $2,474 to $8,024. Difference: A factor of 3.2.

Why the big disparities?

“It would be surprising if everyone was paying the same thing,” said Paul Levy, a former hospital president who writes about healthcare at the blog Not Running a Hospital. (Levy used to blog at Running A Hospital until he left his job at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.)

Explaining how the process worked he said, “When we would negotiate for my place, there was one set of ranges for local insurance companies, which had a great deal of presence in our market. But the national companies, who would just fly by when they had a patient in Boston, we would charge more.”

“It’s all about market power,” he added. The big national insurers like Cigna and Humana had fewer patients, he said, as “price takers,” while local insurers like Tufts, Harvard Pilgrim, and Massachusetts Blue Cross would clump at a lower rate.

“There’s certainly no cost basis for the difference,” he said.

He did add that he is surprised that the reimbursement rates were revealed, even without naming the names of the payers, “because people usually don’t.”

“Early on on the job sometimes I would sit in on the negotiations” between the hospital and insurers, he said. “But then I would stop. Because there was no standard of pricing you could count on. No logic. I would say, ‘What do these rates have to do with our costs?’ because I came from public utility world.”

“They would say ‘we don’t do it that way’ and I would say ‘how do you do it?’ and there was no answer.”

The highest-priced provider in Massachusetts, he noted, is Partners. “Of course they would give Partners anything they wanted, and whatever was left over they would split up among everyone else, depending on how strong Blue Cross felt they were in the market.” (Here’s a link to a 2008 Boston Globe series about Partners and its position in the Massachusetts health marketplace, and here’s a more recent article.)

The role of market power and dominant providers

Market power talks, Levy said.

“It’s pretty much that way wherever there is a dominant provider,” he added.

Looking at the changes in the healthcare landscape, he added, the impetus of mergers and acquisitions is to gain market power over the local insurance company.

Several years ago, during a Massachusetts hearing on healthcare cost trends, Levy blogged about this issue, quoting Andrew Dreyfus, a Blue Cross executive, about market power.

“The State House News Service also said: ‘Andrew Dreyfus, executive vice president of healthcare service for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts — the state’s largest insurer — said he doesn’t believe his company has the market power to eliminate disparities in the way doctors and hospitals are paid for their services,’ ” Levy wrote.

“Blue Cross said it did not have the market power to force the differential to change,” Levy said. “I had to take him at his word. I don’t think they ever tested the proposition.”

“Did it really matter for them? Did they, Blue Cross have a real interest in controlling the rate of increase of premium? The answer is no,” Levy added.

“They get the same percent of profit from every premium dollar. There’s no pressure on them to become efficient over time.”

Further, the Affordable Care Act sets a limit on non-medical costs — the medical loss ratio — that fixes by law the amount of money that insurers must pay out in medical costs, and thus what they can use for other purposes, like management, processing, and so on.

Incidentally, we also noticed a price listing page from the Palo Alto Medical Foundation web site, which lists prices in categories like “diagnostic imaging” and “doctors office visit.” The site explains: “The services below have drop-down menus that show charges for frequently used services provided by Palo Alto Medical Foundation. The amounts you see are the most you would pay before any discounts that may be available to you.” Cost of Services at Palo Alto Medical Foundation.” (PAMF is a division of Sutter Health, a family of not-for-profit hospitals and physician organizations.)

Here’s the finances page from the Sutter Santa Cruz web site. “Uninsured patients receive a 40 percent discount on hospital inpatient charges and a 20 percent discount on outpatient services,” it says. “Uninsured patients who pay their bills within 30 days receive an additional 10 percent discount.”

The academic perspective: Why the secrecy? What to do?

Also expressing interest in the disclosure on insurance reimbursement rates was Jaime King, a law professor and specialist on pricing at the University of California at Hastings College of the Law. The payer was not named, and Rhodeos said she was not sure she could name the payer. King and I spoke on a panel together not long ago; she’s skeptical that transparency alone will benefit anyone.

Payers often cite several reasons for the lack of disclosure. In this blog post, King points out that many times the insurance reimbursement rates are hidden, with enforcement coming either via a claim of trade secrets from the insurer (who doesn’t want the prices made public) or via a confidentiality clause in the contract between payer and provider.

King is a law professor and also the incoming co-director of the UCSF/UC Hastings Consortium on Law, Science and Health Policy, and executive editor of The Source on Healthcare Price and Competition.

So … what’s the answer? What should be done? Massachusetts is trying more regulation of prices, along with a mandate for insurers and providers to reveal pricing — but the state’s health costs are still among the highest in the nation. Periodically, we hear calls for single-payer, though it seems unlikely that single-payer will earn legislative or market approval (look at Vermont’s experience recently). There’s the Blue Cross of North Carolina move to reveal all prices, which is instructive but has not had enormous impact that we can sense. The Republicans are still calling for repeal of the Affordable Care Act, though how that would result in any improvements is hard to see.

And, finally, in our work with PriceCheck in California, our community partnership crowdsourcing prices with KQED public radio in San Francisco and KPCC public radio in Los Angeles, we have learned that prices are all over the map. For an MRI of the lower back, an individual can pay $400, or $6,221, or — with insurance — $1,940, while your insurance company pays $944.97, for a total of $2,885. It seems obvious that some kind of price transparency would be of use here–if not for the provider and the payer, then certainly for the patient.

Jeanne Pinder is founder and CEO of ClearHealthCosts.com, a New York City startup bringing transparency to the healthcare marketplace. Check out the alliance formed between MedPage Today and ClearHealthCosts to tackle price transparency with tools for healthcare providers to join in the effort, and read more in a letter from MedPage TodayEditor-in-Chief Peggy Peck.