I have been working on a paper exploring the link between physician-patient communication and medication adherence and the implications for health care costs. Medication nonadherence among patients is and has been a “gigantic” problem for the health care industry over the last 20 to 30 years… and not just for pharma. Patients outcomes suffer and health care cost sky rocket as nonadherent patients fill ER and hospitals across the U.S.

C. Everett Koop, MD, a former Surgeon General, “summed up” the problem:

I have been working on a paper exploring the link between physician-patient communication and medication adherence and the implications for health care costs. Medication nonadherence among patients is and has been a “gigantic” problem for the health care industry over the last 20 to 30 years… and not just for pharma. Patients outcomes suffer and health care cost sky rocket as nonadherent patients fill ER and hospitals across the U.S.

C. Everett Koop, MD, a former Surgeon General, “summed up” the problem:

“Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

So Why Don’t Patients Take Their Medications?

There are two schools of thought with respect to medication nonadherence. The first holds that nonadherence is a patient behavior problem. Whether it’s because they are stupid, lazy or unengaged…patients just don’t take their medications as directed by their physicians.

The second school of thought holds that nonadherence is often a rational response on the patient’s part when faced with a recommendation to do something they don’t agree with – namely take a medication. There’s even a name for such behavior – it’s called intentional nonadherence. The best example of intentional nonadherence is when patients leave their doctor’s office or are discharged from the hospital and never fill, pick up or take the prescription.

How Can Nonadherence Be Considered Rational Behavior?

I can see how clinicians would feel this way. After all, doctors are acting in the patient’s best interest and prescribe medications because they believe they are necessary. The unfortunate reality however is that patients often fail to see eye to eye with their doctors on the necessity for or the benefits of taking any given prescribed medication.

According to the research, up to 50% of us as patients disagree at one time or another with our doctor regarding a diagnosis, the severity of a condition or safety or efficacy of a particular treatment. Because most patients are loathe to challenge our doctors out of fear of being labeled difficult, we don’t say anything to the doctor. Rather, we just don’t do what they recommend, e.g., don’t fill, pick up or take our medication.

Researchers have shown that, when faced with having to make a health decision, we employ a kind of cost/benefit analysis in our heads. Based up our knowledge at hand – that which we have via our own personal experiences and that which we learn from the doctor, internet, etc. – we assess the “necessity” for taking a recommended action and balance it against any “concerns” we may have as a result of taking the recommended action. If our perceived necessity is greater that our concerns we take the medicine. If our concerns win out….then we don’t take the medicine.

The Role Of Physician-Patient Communication

For the patient’s necessity/concerns calculus to work, patients have to understand and accept that they: 1) have a medical problem, 2) understand that the problem will be serious if left untreated and 3) belief that the recommended treatment is safe and effective. This means that their physician has to take the time to communicate these salient facts to patients in a way they understand and can accept.

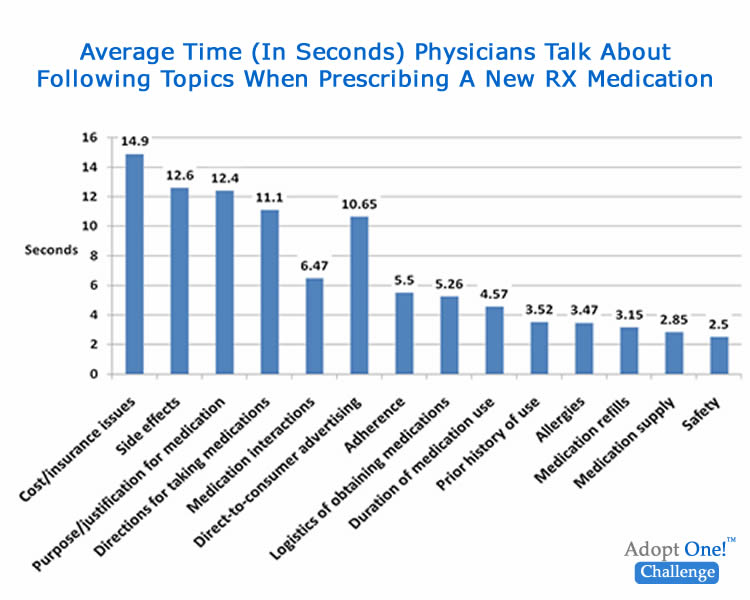

There’s the rub. The average primary care physician spend less than 60 seconds explaining such “ins and outs” to patients during the office visit. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of physician “talk time” by topic during visits in which a new medication was prescribed. To complicate things, patients seldom ask questions of their doctor when prescribed a new medication.

Figure 1

The net result of these limited exam conversations is evident in a 2011 study of low income patient being seen at Cardiology Clinic:

- 55% of patients diagnosed with heart failure “did not recognize” nor agree with their doctor that they had heart failure.

- 85% of patients diagnosed with hypertension disagreed with their doctor’s diagnosis.

- 41% of patients disagree with doctor’s initial diagnosis of a psychological problem

For patients such as those in the 2011 study, given their disagreements with their doctors, the results of their necessity/concerns calculus does not bode well for their being adherent patients should medications be prescribed.

The Take Away

Physicians tend to overestimate the amount of health information they give patients and underestimate patients’ desire for information.

Clinicians and provider organizations interested in improving patient adherence and reducing preventable ER visits and hospital admission (and readmits) should invest in assessing and improving their patient communication skills as well as those of the physicians in their provider network.

The evidence suggests that patient medication adherence could be improved 10% – 20% with such interventions. This translates into much improved patient outcomes and significant cost saving.

That’s my opinion…what’s yours?

Sources:

Ho, P. M., Bryson, C. L., & Rumsfeld, J. S. (2009). Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation, 119(23), 3028–35.

Sokol, M. C., Mcguigan, K. A., & Verbrugge, R. R. (2005). Impact of Medication Adherence on Hospitalization Risk and Healthcare Cost. Medical Care, 43(6), 521–530.

Tarn, D. M., Paterniti, D. A., Kravitz, R. L., Heritage, J., Liu, H., Kim, S., & Wenger, N. S. (2008). How much time does it take to prescribe a new medication? Patient Education and Counseling, 72, 311–319.

Sarkar, U., Schillinger, D., Bibbins-domingo, K., Na, A., Karliner, L., & Pe, E. J. (2010). Patient Education and Counseling Patient – physicians ’ information exchange in outpatient cardiac care : Time for a heart to heart?