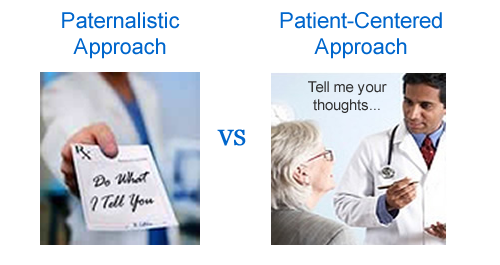

If patient-centered care is supposed to be about “respecting the patient’s perspective” where possible, as well as a measure of high quality health care, then why are RWJF and the Center for Connected Care teaming up to “convince” people to do what they have shown they don’t want to do? That’s provider-centered care (aka beneficent paternalism), not patient-centered care.

In a recent announcement, the Robert Wood John Foundation announced a $468,000 grant to the Center for Connected Health to develop an “engagement engine” to “convince” consumers to use health and activity trackers and other health apps.

Why? According to the announcement:

Few [consumers] are using them [health apps] beyond a couple months. And that’s why providers are hesitant to jump on the bandwagon

The marketing logic is clear enough. RWJF and Connected Health believe they need to get more patients to use health apps, so that they will then tell their doctors about the apps, in the hopes that doctors will then recommend the apps to other patients. What is not clear is why RWJF and Connected Health are “doubling down” on health apps in the first place. It is not like the consumer market is tripping over themselves to use them, with the possible exceptions of the quantified self users.

Does RWJF or Connected Health really believe that “putting new wine in old wine skins”, e.g., an engagement engine, is somehow going to make all these discarded or unused health apps more desirable to consumers and physicians? Isn’t it just possible that maybe consumers have good reasons for not wanting/using health apps, reasons like lack of product relevance, lack of product value/usefulness, ease of use and so on?

Let’s consider the issues of relevance and usefulness:

Relevance – Many providers believe that most people (patients) today are generally “unengaged” in their health. Why? It is because patients don’t do what they are told to do by providers. After all, doctors have the best interests of their patients in mind when they tell them to exercise, lose weight, etc. When patients are nonadherent, it’s because they don’t care; they are unengaged. By extension, developers of health apps – who often include physicians – think about patients the same way. It never occurs to providers or developers that patients might have good reasons for their nonadherence, i.e., they don’t agree with treatment recommendation, don’t understand what the doctor told them to do, can’t do or afford to do what the doctor recommended and so on.

I would go even further in saying that many provider (and health app developers) have disdain for patients and their cognitive ability to understand things pertaining to their own health.

Consider the following quote from Joe Kvedar, MD, of the Center for Connected Health Care, which is the beneficiary of the RWJF grant:

In healthcare, we can’t just give people what they want. The challenge in healthcare is that, though we [physicians] know what patients/consumers need to do to improve their health, most of them don’t want to hear about it.”

Privately, in meetings and conferences about patient engagement, we have all heard how patients (that us folks) are fickle, dumb, lazy, unengaged, or otherwise incapable of understanding what it is they should be doing when it comes to their health and health care. This line of thinking shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. This paternalistic, “I know best” style is how most doctors communicate with and relate to patients today. It’s how doctors were taught in medical school to relate to patients .

Now juxtapose this paternalistic, physician-centered “view” of patient engagement with the patient’s perspective, e.g., patient-centered perspective.

Fact: Over 80% of US adults see their doctor at least once a year – the national average is 3 visits/year – double that for patients with a chronic condition.

Now what is it about these statistics that “screams” unengaged? Why would so many people who are so “unengaged” spend so much time making and waiting for an appointment to do something they care so little about? They wouldn’t!

Fact: Patient have their own ideas of what constitutes “health” and they have their own ideas and preferences for how best to achieve their health goals.

But since providers seldom solicit the patient’s perspective, the patient’s beliefs and motivations tend to get lost during the medical exam. Health apps are no different. A patient that doesn’t like to take pills will balk at a recommendation to take an Rx medication. A person who lives in an unsafe neighborhood will cringe at being to walk the dog around the block to lose weight. You get the idea.

Is it any wonder that health apps designed from a paternalistic, physician knows best point of view do little more than disengage consumers that consider themselves knowledgeable and engaged?

Usefulness – How many of us have been asked by our physician at one time or another to record some aspect of our health behavior like our blood pressure? I know I have and I also know how it felt when the doctor never asked to see the results at a follow-up visit. What a waste of time.

Patients know from experience that physicians will probably never pay any attention to the data collected by a health tracking app. If my doctor never bothered to ask about my BP that I recorded (at his request) so diligently on an Excel spreadsheet…why will they care about the data captured by Fitbit?

Physicians, for their part, are already overwhelmed with more data than they know what to do with. Since many doctors’ EMRs don’t “play well” with the hospital’s EMR system, is it little wonder that physicians are not terribly excited about paying to add more health app interfaces to their EMR?

Unless and until the data from health apps can be seamlessly integrated into the patient visit record…and physicians actually do something with the data for the patient’s obvious benefit…both physicians and patients will fail to see the usefulness of health apps (and portals).

My suggestion to RWJF and Connected Health is to step back and consider the relevance and usefulness of health apps from the consumer’s perspective before trying to “convince” or “sell” consumers of their value. Also, lose the “doctor knows best” message in favor of a “patient knows best” message that acknowledges the patient’s ability to decide what’s best for themselves. Telling your target market how dumb they are is never a good marketing strategy.

If you need help…you know where to find me.