(Public domain) Researchers from the Max Planck Institute discover how the supramarginal gyrus helps us distinguish our own emotional state from that of others and so enables us to feel empathy.

Those who possess even a modicum of self-awareness understand that their own feelings can get in the way of empathizing with others. Now a research team headed by Tania Singer from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences has located the exact area of the brain that helps us distinguish our own emotional state from that of others and so enables empathy. It is the supramarginal gyrus, a convolution of the cerebral cortex which is located roughly at the junction of the parietal, temporal and frontal lobe.

“This was unexpected, as we had the temporo-parietal junction in our sights. This is located more towards the front of the brain,” Claus Lamm, one of the study’s authors, explained in a press release.

Experiment and Discovery

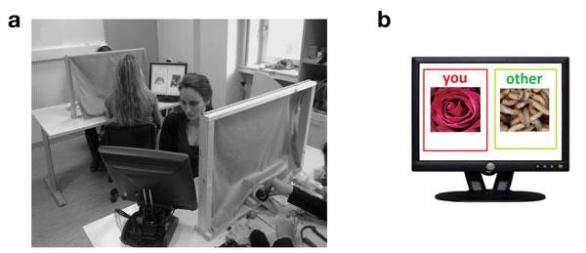

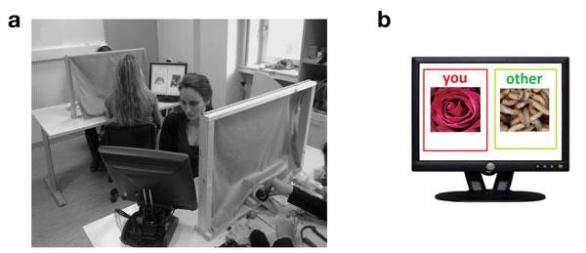

By way of a perception experiment, the researchers began by showing that egocentricity can be measured. The participants, who worked in teams of two, were exposed to either pleasant or unpleasant simultaneous visual and tactile stimuli. While one participant, for example, looked at a picture of maggots and with her hand felt slime, another participant looked at a picture of a puppy and felt on her skin a soft, fleecy fur.

“It was important to combine the two stimuli,” Lamm explained in a press release. “Without the tactile stimulus, the participants would only have evaluated the situation ‘with their heads’ and their feelings would have been excluded.”

The two participants were then asked to evaluate either their own emotions or those of their partners. As long as both participants were exposed to the same type of positive or negative stimuli, they found it easy to assess their partner’s emotions. (During the experiment, the participants were aware of the stimulus to which their team partners were exposed.) The participant who was confronted with a stinkbug could easily imagine how unpleasant the sight and feeling of a spider must be for her partner.

Differences arose when one partner was confronted with pleasant stimuli and the other with unpleasant ones. In such cases, participants’ capacity for empathy suddenly plummeted. The participants who were feeling good themselves assessed their partners’ negative experiences as less severe than they actually were. In contrast, those who had just had an unpleasant experience assessed their partners’ good experiences less positively.

Scanning the Brain for Answers

With the help of functional magnetic resonance imaging, the researchers were able to identify the area of the brain responsible for this shifting ability to feel empathy. When the neurons in the right supramarginal gyrus were disrupted in the course of this task, the participants found it difficult not to project their own feelings onto others. The researchers observed that participants’ assessments were also less accurate when they were forced to make quick decisions. They deduced the right supramarginal gyrus served to ensure an individual can decouple his or her perceptions from that of others. In other words, an additional function performed by the brain is needed to avoid biased social judgments in other situations.

“Our study extends previous models of social cognition,” the authors wrote in their paper published in the current issue of Journal of Neuroscience.

Source: Silani G, Lamm C, Ruff CC, Singer T. Right Supramarginal Gyrus Is Crucial to Overcome Emotional Egocentricity Bias in Social Judgments. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013.